This is not based on any kind of rigorous methodology; these are just the books I enjoyed and/or that “stuck with me” the most throughout the year. As should be obvious, these were not necessarily books published in 2013.

Fiction:

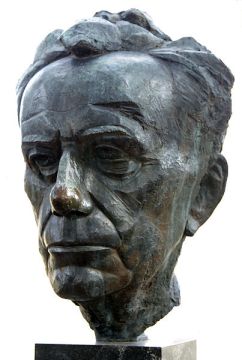

Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy

I decided to start reading this late last year after seeing the film version starring Keira Knightley. I’m frankly in awe of it, and nothing I can say will do it justice. But the thing that probably struck me the most was Tolstoy’s ability to draw fully realized characters and make the reader truly view the world from their perspective (including, in one case, a dog!). I can see why some people have compared Tolstoy to God: he intimately knows and truly loves each of his characters (sometimes, one senses, in spite of himself). And I haven’t even mentioned the delicately intertwining stories, the astonishingly clear and beautiful scenes Tolstoy draws, the social commentary, and the philosophical and religious musings. Basically, this book deserves every bit of its reputation as one of the greatest novels ever written.

True Grit, Charles Portis

I’d seen both movie versions, but had never read the book. Portis’s unforgettable characters, deadpan dialogue, and tightly constructed plot made this a hugely enjoyable read.

Non-fiction:

The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics, James Oakes

Oakes’ recounting of how the radical abolitionist Douglass and the temperamental conservative Lincoln converged around a particular brand of antislavery politics isn’t just a fascinating story about two important figures at a pivotal point in American history (it is that, though!). It also serves as a rebuttal of sorts to radicals of every stripe who think they’re too pure for the grubby business of electoral politics.

Systematic Theology, vols. 1 and 2, Paul Tillich

I disagree profoundly with some of Tillich’s basic theological positions, but his thought remains, nearly 20 years after I first read him, a source of stimulation and insight.

Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America, Garry Wills

I’m not sure Wills persuaded me of his main thesis, namely, that Lincoln’s address at Gettysburg was, in effect, an ideological re-founding of the Republic. But his erudition is undeniable, and his analysis of the address in light of classical and contemporary examples of funeral oratory is extremely illuminating. He also writes like a dream.

Unapologetic: Why, Despite Everything, Christianity Can Still Make Surprising Emotional Sense, Francis Spufford

Spufford avoids nearly every cliche of contemporary religion writing and provides the freshest take on Christian faith I’ve read in ages. Sharp, funny, and heartfelt without being sappy. As I said in my “non-review,” I think Spufford captures how many of us in the “post-Christian” West experience our faith.

How Much Is Enough?: Money and the Good Life, Robert Skidelsky and Edward Skidelsky

This father-and-son team (an economist and philosopher, respectively) ask why the richest societies in history have so much inequality and so little genuine leisure. They blame a combination of political and philosophical failures, and argue for recovering a broadly Aristotelian concept of the good life than can help us get off the production-and-consumption treadmill. Their skewering of trendy “happiness” research and its associated policy prescriptions alone is worth the price of admission. Also worth noting is their critique of liberal “neutrality” regarding the good life.

I’ve got a couple of books going now, and if any finish any before December 31st that blow me away, maybe I’ll update this. Also, looking this over, I realize that I really need to read more books not written by white men.