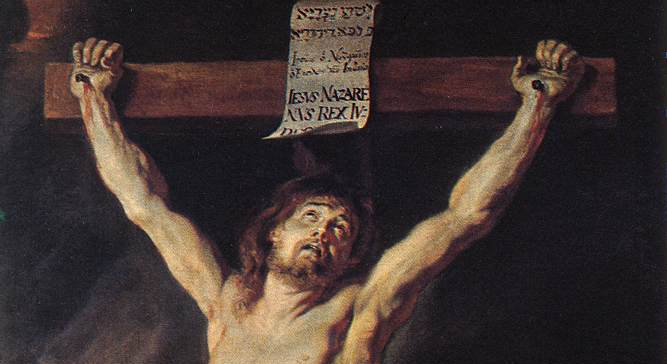

Is the Christian gospel about the life and teachings of Jesus, or is it about his death and resurrection? These two poles of the Christian message have often been pitted against one another, sometimes in the form of St. Paul’s “theology of the cross” vs. “the Jesus of the gospels” (particularly the synoptic gospels).

In her brief but rich book Not Ashamed of the Gospel: New Testament Interpretations of the Death of Christ, esteemed New Testament scholar Morna Hooker argues (persuasively, to my mind) that the NT authors were largely on the same page regarding the significance of Jesus’ crucifixion and its implications for Christian living, even though they might differ somewhat in emphasis.

Hooker dedicates successive chapters to the though of Paul, each of the four gospel writers, the letter to the Hebrews, and 1 Peter/1 John/Revelation. These authors use a variety of metaphors, images and concepts to express the meaning of Jesus’ death (and resurrection), and one would look in vain for a fully developed “theory of atonement.” Nevertheless, Hooker shows that there’s a remarkably consistent set of assertions that are virtually unanimous among these witnesses:

- “Jesus was put to death through the weakness and sin of wicked men and the rebellion of satanic powers, [but] it was part of God’s plan, and took place in accordance with scripture.” (p. 139)

- “Through Christ’s death and resurrection God has reconciled us to himself.” (p. 139)

- “That Jesus suffered ‘for us’ does not mean that Christians can expect to escape suffering themselves — the very opposite! Christ triumphs over death, but those who want to share his triumph must share his shame and suffering and death.” (p. 140)

- “It is not simply the absurdity of the gospel itself — a crucified Messiah!– which might cause Christians to blush, but its implications for the life-style of those who commit themselves to following a crucified Lord.” (p. 140)

That Jesus’ death is part of the divine plan and the site of divine forgiveness goes against certain liberal theologies that are uneasy with the idea of God using such gruesome methods to redeem humanity. At the same time, Hooker insists that the cross is no mere “substitution” whereby Jesus suffers instead of us. She prefers the language of “participation”–we are saved through union with Christ in his dying and rising. This has implications for how we live–Christians must expect to suffer as part of following a crucified messiah. This rules out certain individualistic interpretations of Christianity that peddle Bonhoeffer’s “cheap grace” and downplay the cost of discipleship. And how far from the spirit of the NT are the various “prosperity gospels” that promise an untroubled life of material success and contentment!

In other words, talking about the gospel as either a religion of redemption and forgiveness or a way of life modeled after the example of Jesus is a false dichotomy. Hooker seems to find the image of participation the most compelling way of expressing this: God in Jesus became like us so that we can become like him. This isn’t a simple “exemplarist” understanding of salvation; it’s more like a mystical union with Christ whereby we share in his righteousness and are (re-)formed in his image.

Ultimately, Hooker says, the revelation of God’s glory in the cross is the deepest meaning of the NT witness:

The idea — common to Paul and John — that God’s glory is revealed in the death of Christ is perhaps the New Testament’s most profound insight into its meaning. … The belief that God is revealed in the shame and weakness of the cross is a profound insight into the nature of God. … By embracing the scandal of the cross, and joyfully accepting its shame, these early Christians discovered the true character of God, and found that the true source of joy consisted in becoming like him. (p. 141)